terry bouch, Bigstockphoto

Evertonians like to sing a song that begins, “And if you know your history…” It’s a song about how they don’t care what Liverpool supporters say, but that their hearts glow when they think of Everton’s glorious past. Perhaps that’s because their past is so inescapably intertwined with the history of Anfield? There’s never any real point in trying to figure out what Bluenoses are thinking from one minute to the next, to be honest…

Here, though, I’ll guide you through the history of Anfield as a stadium. We’ll go from the dark days when Everton used to play their football on our hallowed turf right the way through to the modern era. I’ll tell you about the changes that have taken place in the stadium over the years and also inform you about some of Anfield’s most famous nights. Whether you’ve been a season ticket holder for years or you dream of one day entering the Kop and singing songs about the Red men, hopefully I’ll be able to teach you something you didn’t know before.

From Humble Beginnings

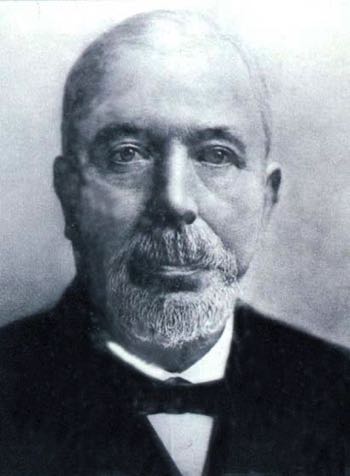

John Houlding (Wikipedia)

Anfield first opened its doors in 1884 when John Orrell, a land owner and mate of Everton Football Club member John Houlding allowed the Blues to use it in exchange for a small fee. The very first match on the Anfield turf was a 5-0 victory for Everton over Earlestown and took place on the 28th of September 1884.

Over the years more than 8000 people would regularly turn up to watch the Toffees play – so a similar amount to nowadays – and eventually a decision was made to put up stands to house them all. By 1889 the ground was considered to be good enough to host international matches, with England’s game against Ireland in that year’s British Home Championship taking place there. That was nearly a year after the first league game took place in the ground; Everton took on Accrington on the 8th of September 1888.

The Blues were actually the first side to win a league championship whilst playing their games out of Anfield. They won the 1890-1891 campaign, becoming champions of England for the first time. the club’s success meant that a decision was made to buy the land where the ground was located from John Orrell, and that was the moment that history would change for the better. The negotiations led to a disagreement about how Everton Football Club was run between Houlding, who had introduced the club to the ground in the first place, and the club’s committee.

Eventually, for numerous reasons that are too complex to be bothered to go into, Everton left Anfield and set-up their own stadium at Goodison Park. That left Houlding with a stadium but no club to use it. His only choice was to form a new club that he could run any way he saw fit. Liverpool Football Club and Athletic Grounds Ltd. was born, playing its first match at Anfield on the 1st of September 1882; a friendly against Rotherham Town that the new team won 7-1. Liverpool won their first league match at the ground, too – a 4-0 victory over Lincoln Town that was witnessed by more than 5000 people.

Expanding the Stadium

The success of the new club meant that Anfield needed to be expanded. Accordingly a new stand, capable of housing around 3000 people, was built in 1895 where the Main Stand is today. Designed by the renowned football architect Archibald Leitch, the stand boasted a distinctive red & white wall that was reminiscent of the black & white one at Newcastle United’s St. James’ Park.

By 1903 the stadium needed to be expanded again and so another stand was built at the Anfield Road end of the ground. Arguably the most important development of Anfield happened three years later when a stand was built along the Walton Breck Road of the stadium, It came on the back of Liverpool winning their second league title in 1906. The stand itself wasn’t all that remarkable, but what has stood the test of time was the name that was given to it by a local journalist.

Ernest Edwards was the sports editor for two local papers. the Liverpool Daily Post and the Echo.He christened it the Spion Kop as a dedication to the hundreds of men, many of whom were from Liverpool, who had lost their lives in the battle at the hill with the same name in South Africa during the Boer War. Over the years the word ‘Spion’ was dropped from the name, but it has been called ‘The Kop’ ever since.

A stand was built along the Kemlyn Road at about the same time as the Kop was erected, meaning that Anfield become something of a formidable ground for away teams to visit. It remained that way until 1928 when the Kop was redesigned to become even more intimidating. 30,000 people could now enter it and stand to watch football on a match day. It meant that more people could fit inside one grandstand at Anfield that could be housed in entire stadiums elsewhere in the country.

Entering the Modern Era

Shankly Gates (Andy Nugent, Wikipedia)

Liverpool’s success as a football club was mixed over the years, but the evolution of Anfield continued wherever possible. In 1957 a decision was made to erect floodlights at the stadium, costing the club £12,000. Fittingly they were used for the first time in a match against Everton. It was a friendly game to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the formation of Liverpool’s County Football Association.

Further changes took place in 1963 when the ageing Kemlyn Road Stand was knocked down. A new cantilevered stand was built in its place, costing Liverpool £350,000 and capable of welcoming 6700 people through its doors. In 1965, as The Beatles were taking the world by storm and Liverpool became the centre of the universe, the Anfield Road End gained a roof and became a standing area.

Perhaps the biggest change to date at Anfield came about in 1973 when the Main Stand was completely demolished in order to make way for a new, more modern structure to be erected in its place. The old floodlights, installed at such expense sixteen years before, were removed in order to be replaced by newer floodlights put along the roof of the Kemlyn Road Stand and the newly built Main Stand.

The 1980s saw further changes to various parts of the ground, both inside and out. To begin with the Paddock area at the front of the Main Stand was changed from being a terrace section into a seated area. In 1982 seats were installed at the Anfield Road End, too. During that same year a tribute was made to the father of modern day Liverpool. Bill Shankly dreamed of turning Anfield into a ‘bastion of invincibility’ and boy oh boy did he see his dream realised.

Shanks passed away on the 29th of September 1981. Just under a year later, on the 26th of August 1982, his widow Nessie unlocked the newly installed Shankly Gates for the first time. Written across the top of the gates are the words from a song that had been adopted by the Liverpool supporters as the club’s unofficial anthem during the Scotsman’s time as manager: You’ll Never Walk Alone.

The Aftermath of Hillsborough

Hillsborough Memorial (Damine178, Wikipedia)

On the 15th of April 1989 Liverpool supporters travelled to Hillsborough Stadium in Sheffield to see their team take on Nottingham Forest in the FA Cup semi-final. Owing to a series of critical errors in the running of the event by South Yorkshire Police, a disaster unfolded on national television that resulted in 96 people losing their lives. No words here can adequately express what happened that day, nor explain the second tragedy that unfolded in the wake of the disaster as the families and loved ones of the victims were made to wait decades for justice to be served. No one should ever go to a football match and not return home. No one should see the trust they place in the authorities to look after them so cruelly abused.

In the wake of the disaster a decision was taken by Kenny Dalglish, the manager at the time, to throw open the doors of Anfield to the people of Liverpool, allowing them to pay tribute to those that had lost their lives. Thousands of fans turned up from virtually every club in the country, filling the stadium with flowers, football scarves, football shirts and other tributes. More than 200,000 people passed through the doors of Anfield in the immediate aftermath of the Hillsborough Disaster. A link of scarves was created from Anfield to Goodison Park, covering just under a mile. The final scarf was put in place at 3.06pm, the exact moment that the referee abandoned the match the week before.

Lord Justice Taylor was asked to investigate the causes of the Hillsborough Disaster. In 1989 an interim report was released, with the full report published in 1990. The report made clear, even then, that Liverpool fans were in no way whatsoever responsible for the disaster and that police failings were the major cause of the problems that occurred in Sheffield on that fateful day. Taylor was asked to make recommendations to help avoid a similar disaster occurring in the future and the suggestions he made would change not only Anfield but the face of football as a whole.

The major change that Lord Justice Taylor suggest be implemented was the conversion of all major stadiums into all-seated affairs, removing the terraced sections that allowed supporters to stand. Each and every supporter entering a stadium to watch a match should, said Taylor, have a ticket in order to do so. Though he did not say that all standing areas were unsafe, the government decided to ban them anyway. He also said that clubs should not be allowed to use the conversion to all-seater stadia as an excuse to price fans out of the game, but this has also been widely ignored by clubs ever since.

Conversion to All-Seater

coward_lion, Bigstockphoto

In the wake of The Taylor Report the government insisted that all stadia be turned into all-seater arenas by May of 1994. Consequently Liverpool Football Club had to begin the expensive and arduous task of doing just that. From a financial point of view the club was slightly fortunate that it had already made the decision to add seating to the Anfield Road end and to the Paddock area of the Main Stand during the 1980s. In 1992 a second-tier was added to the Kemlyn Road Stand, making it a two-tier grandstand. It was also renamed in honour of the fact that the club was 100-years old, becoming the Centenary Stand when it was officially re-opened on the 1st of September.

The last game to be played in front of the Kop took place on the 30th of April 1994 when Norwich City came to Anfield. It ended in a 1-0 defeat but that seemed largely irrelevant to everyone inside the stadium that day. Legends of the club, from Tommy Smith to Phil Thompson, Kenny Dalglish to Billy Liddell, were paraded in front of the famous old stand to roars of approval from those lucky enough to get tickets inside. The names of Shankly and Paisley were sung with pride.

In its heyday the Kop regularly welcomed around 30,000 supporters through its doors. The conversion of the grandstand to being an all-seater reduced this to 12,390. It completed the changes made to Anfield in order to comply with The Taylor Report and many people feared that the once famous atmosphere of Anfield, instigated by the voices on the Kop, would be lost for good. That turned out to be a fallacy, thankfully, as I’ll explain a little later.

Other Things of Note

This is Anfield (coward_lion, Bigstockphoto)

The problem with a look at the history of Anfield is that you’ll almost certainly miss some things unless you can make it a limitless project. Sadly I can’t and I’m not sure you’d be all that interested in reading this if it was 30,000 words long. I’m keen to try to capture all of the most noteworthy things at Anfield, though, and so this is my chance to do just that.

The Paisley Gates

If Bill Shankly was the founder of modern day Liverpool then Bob Paisley was the man who learnt from his boss and took things to the next level. The most successful British manager of all-time, Paisley died on the 14th of February 1996 and, much like with Shankly, his life was commemorated and honoured with the installation of the Paisley Gates at Anfield.

This Is Anfield

When both teams walk out of the dressing room and line up to head down the tunnel and on to the pitch a big red sign with Liverpool’s crest on it greets. Them. It says ‘This Is Anfield’. Bill Shankly first installed the sign during the 1960s and claimed that it was to ‘remind our lads who they’re playing for and to remind the opposition who they’re playing against’. During the redevelopment of the Main Stand it was taken down for the first time in decades.

The Hillsborough Memorial

In the wake of the Hillsborough Disaster it was decided that it would be appropriate for the club to install a memorial to the victims so that their families and loved ones would have somewhere to pay their respects. An eternal flame was lit and a plaque was erected with all 96 names of those who lost their lives engraved on it. This was moved into storage during the redevelopment of the Main Stand, but was returned in August of 2016. It now sits in a specially designed colonnade, with a tree lined walkway leading up to Anfield named ’96 Avenue’.

The Shankly Statue

An eight foot statue of Bill Shankly was unveiled in front of the Kop on the 4th of December 1997. It depicts the Liverpool great with his arms outstretched in celebration. The plinth underneath bears his name as well as the inscription ‘He Made The People Happy’.

Famous Anfield Nights

Cosmin Iftode, Bigstockphoto

Despite the relative disappointment on the pitch in recent years, Liverpool Football Club has been witness to some incredible nights over the years. You may well have your own favourite, but here are some of the ones that stand out to me:

Liverpool 3 – St. Etienne 1

Liverpool travelled to France for the first-leg of the quarter-final of the European Cup in 1977. They lost 1-0 and the lack of an away goal led many to believe the Reds might struggle at Anfield. Kevin Keegan gave Liverpool the lead but an equaliser in the 50th minute meant that the Reds needed to score two to progress. Ray Kennedy scored the first before David Fairclough, the ‘super sub’ netted the second with six minutes remaining on the clock.

Liverpool 3 – Olympiakos 1

Liverpool’s march to Champions League glory in Istanbul in 2005 was moments away from never happening. It was the final match of the group stage of the competition and the head-to-head record between the Reds and Greeks meant that Liverpool needed to win by two clear goals. An early one for the visitors meant that the Reds needed to net three times in 64 minutes without reply or they would be out. Florent Sinama-Pongolle scored the first before Neil Mellor grabbed the second with nine minutes remaining. Who else but Steven Gerrard could score the winner?

Liverpool 1 – Chelsea 0

Rafa Benitez had pulled off a tactical masterstroke in the first-leg of Liverpool’s Champions League semi-final against Chelsea. A 0-0 against José Mourinho’s men made it clear exactly what needed to be done. The Kop produced enough noise to cause the Chelsea players to lose their ability to even pass the ball, with the roof being lifted off when Luis Garcia’s shot was adjudged to have crossed the line.

Liverpool 4 – Borussia Dortmund 3

A 1-1 draw at the Westfalenstadion was enough to give Jürgen Klopp hope that his embryonic Liverpool side could progress to the semi-final of the Europa League against his former club Borussia Dortmund. Two goals in the opening nine minutes at Anfield silenced the crowd, with Marco Reus making it 3-1 with 33 minutes to play. Coutinho made it 3-2 before Sakho got the equaliser. In stoppage time Dejan Lovren nodded in the winner and Anfield was the noisiest it had been since the 1970s.